Three ways to reduce UK's £22bn debt

Higher taxes or lower public spending? Assessing the different options available over the next five years.

Based on Treasury figures, UK net debt is likely to rise to 80pc of GDP over the next five years as a result of the economic slump. According to various outside forecasters, including the International Monetary Fund and Standard & Poor's, the public debt burden could swell towards 100pc, at which point the UK could start having trouble financing itself in the capital markets.

On the basis that the Government must take action to cut the deficit, or be forced to do so by the threat of a gilt strike, The Sunday Telegraph has assessed the different options available over the next five years. The outlook is not rosy but the sooner both we and the politicians face up to the necessary sacrifices the better.

The Government has been told to find "more ambitious" plans to cut its deficit over the next few years. As things stand, the Treasury pledges to bring the Budget back into balance (in other words no longer running up net debt) by 2017/18 - beyond the end of the next Parliamentary term.

A reasonably more ambitious plan might be to bring this forward to 2015/16, in other words to bring the Budget into balance and start chopping away at net debt by the end of the next Governmental term.

The target is £22bn of cuts in the current Budget (beyond the cuts to investment projects, such as Crossrail or Trident) by 2013-14, according to calculations from PricewaterhouseCoopers.

MENU ONE: HIGHER TAXES

Starter

£7bn Increase VAT by 1.5pc to 19pc. Raises £7bn

The VAT rate is already set to rise back to 17.5pc at the end of this year but a number of accountants, including BDO Stoy Hayward, have identified this consumption tax as the easiest tax to raise. Britain's VAT rate is low in comparison with most European countries and the Government could probably pass the cut on as a reasonable attempt to keep consumption, which rocketed ahead during the debt bubble, under control.

Main course

£10bn Increase the basic rate of income tax by 2p. Raises a further £10bn.

Ouch. Not a popular move you'll probably agree but, if you need to raise a sum on the scale that the Government does, such radical moves may prove necessary. Research from the Institute for Fiscal Studies has shown that any attempt to increase revenue with higher tax rates for bigger earners may be forlorn, so an increase in the basic rate may be the best option. However, economists have pointed out that the overall tax burden is already higher than it ought to be. There is a major risk that a big tax increase could drive both consumers and businesses out of the country.

Dessert

£5bn Increase National Insurance contributions from employees and employers by half a percentage point. Raises £5bn.

The Government has already announced a series of NI rises: from April 2011 both classes of NI will rise by 0.5pc, raising £5bn. The Government could double this increase in one fell swoop at the risk, again, of infuriating taxpayers and businesses. After all, NI is little more than a disguised version of income tax.

MENU TWO: HIGHER TAXES AND LOWER PUBLIC SPENDING

Starter

£4.5bn Trim pensions and benefits in the public sector. Saves about £4.5bn.

According to Carl Emmerson of the Institute for Fiscal Studies, government plans to restore the link between the basic state pension and average earnings will cost £0.7bn in 2012-13; £1.4bn in 2013-14 and even more thereafter. It could reduce the generosity of tax credits for better off families with children, raising £1.4bn. Cutting the subsidy to student loans would save over £1.5bn.

Main Course

£4.6bn VAT might be the easiest and least politically damaging tax to increase. Raises £4.6bn

A 1pc rise on VAT to 18.5pc next year (don't forget that the current VAT cut will expire at the end of the year) will raise £5bn. Remember also that in documentation mistakenly released in the wake of last autumn's pre-Budget report, the Treasury revealed that it had considered raising VAT to this level anyway at the end of this year. It is clearly something Whitehall economists think would be

feasible. And don't forget that the Conservatives have also increased VAT.

Dessert

£12bn Extra departmental spending cuts. Saves £12bn.

The Government is already factoring in some hefty cuts in Government spending. However, these may have to be taken one step further if the Treasury is to make an indent in the deficit in the next half-decade. A 3.4pc real terms cut in departmental expenditure limits would help save a massive £12bn. However, no major Government has achieved such significant cuts in recent history. If the Tories intended to save £12bn while safeguarding the health and international development budgets it would involve eye-watering 5pc cuts in every other department.

MENU THREE: VAST CUTS IN PUBLIC SPENDING

Starter

£10bn Cut public sector wages by 5pc. Saves about £10bn

There is a growing appetite (at least within the private sector) for a cut or a freeze in public sector salaries. In the private sector, wage bills are already falling as workers take enforced holidays or pay cuts. Wage deflation is likely to become one of the big stories of the next year. Against this backdrop, a reduction in public servants' salaries might seem sensible, if politically difficult to carry out. Freezing the wage bill could save upwards of £3bn every year the policy was enforced. A real cut would be even more dramatic.

Main course

£12bn Ambitious departmental spending cuts. Saves £12bn.

As above, if tax rises are to be avoided, the Government will have to impose some unprecedented discipline on its budgets. A 3.4pc cut in departmental expenditure limits, which would raise £12bn, would not need to be shared equally between every department, but some, perhaps the Home Office, Education or Health, will have to suffer major cuts, which in turn would result in a significant dent to front line public services. There are no free lunches in a fiscal crisis.

Dessert

Pensions reform. Savings minimal until 2014 but potentially massive thereafter.

The fiscal crisis associated with this recession is but a prawn cocktail in comparison with the budget chateaubriand that is Britain's pensions and demographic crisis. In the long-run, the effects of ageing and poor pensions planning mean the deficit will keep rising unless we do something drastic.

Ray Barrell of the National Institute for Economic and Social Research proposes raising the retirement age to 70 within the next decade, which by 2023 would be the equivalent of raising income tax by 15p - without the instant hit on consumption of a tax rise.

Britons will be poorer in coming decades

Britain's economic crisis is still with us and is going to worsen. Some unpleasant medicine will have to be taken.

Chances are you are already bored to death with the endless debate on public spending and the fiscal deficit. For weeks, Labour and Conservatives have traded blows in Parliament over the extent to which the other will cut its spending plans. The next chapter is likely to concern tax rises, as the Tories lay into the Government for hiding their planned increases after the election. But, like it or not, the budget and its parlous state will remain one of the most contentious and hotly-debated topics next year.

The reason is very simple. The combined effect of the financial crisis and recession has been to generate a deficit the likes of which has not been since since the aftermath of the Second World War. Britain's total public sector net debt will be catapulted from a level of below 40pc last year to around 80pc or perhaps 100pc and beyond.

In part, this is due to the extra cash needed for unemployment benefits, bailing out stricken banks such as HBOS and Royal Bank of Scotland and temporary Keynesian tax cuts and spending increases. But the greater part of the black hole is due to the fact that a massive chunk of the tax revenue the Government assumed would keep flowing into its coffers has simply dried up, mainly because the golden goose that was the City is no longer so prodigious.

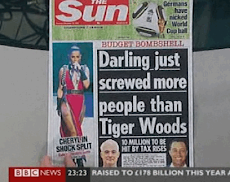

The economic gravity is irresistible. Whoever wins the next election will, whatever their manifestos say, have to inflict swingeing cuts on public spending or raise taxes significantly. Whereas in previous years Gordon Brown could get away with borrowing more each year to keep his Budget ticking over, this option is now under the most severe threat since the mid-1970s, when Britain was bailed out by the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Ratings agency Standard & Poor's has warned that unless Alistair Darling finds "more ambitious" fiscal plans, it will probably cut the UK's credit rating.

If it does so, Britain faces a slippery slope of ever-increasing interest costs on its debt, a growing struggle to raise finance from international creditors and, if matters deteriorate further, the prospect of a full-scale financing crisis.

According to Ray Barrell, chief UK economist at the National Institute for Economic and Social Research, Britons will have to come to terms with the fact that the UK will be poorer in the coming decades.

"This means there's a strong case for cutting back on public sector investment beyond the already weak projection in the Budget," he says. "I can't imagine we'll see as large a programme of public investment as people expect – which means that things like Crossrail [which is estimated to cost around £16bn] and nuclear weapons system Trident [whose replacement cost is estimated at £40bn] are under major threat, whichever political party is in power."

However, although cutting investment projects such as these or the introduction of ID cards will help bring the total net debt figure down, a more pressing need is to bring current spending, the outflow of annual cash for existing public sector programmes, down. After all, Crossrail and Trident aside, the Government is already planning a massive cut in investment in its current Budget plans. According to John Hawksworth of PwC, the Government needs to find a further £22bn in savings or revenues by 2013-14 in order to bring the current budget back in balance by the end of the next electoral term.

To do so would involve some major sacrifices, he says: "If you did everything by cutting spending and raised no extra taxes, our estimate is that departmental spending might need to be cut by 11pc in real terms by 2013."

The Institute for Fiscal Studies predicts a slightly more modest squeeze of 7pc but both would represent public service cuts of a type never before achieved by a UK government. Although the Thatcher government cut the size of the state, partly through privatisations, it balked at the challenge of imposing cuts such as this on its core welfare state functions.

The Sunday Telegraph has mapped out three possible paths for public spending and taxes. They underline the scale of the potential tax rises or spending cuts that would bring the budget back towards balance - and even then only within five years. The plain fiscal logic is that there is no easy way out of this.

Moreover, the impact of the recent crisis is only one half of the issue. The UK also faces a more serious long-term crisis, thanks to its demography. The ageing of the population, in conjunction with the effect of imprudently generous pensions policies, means Britain's national debt could rise yet further to 200pc of GDP by 2050, according to S&P calculations. NIESR's Barrell says this means it is essential to tackle the impending black hole as soon as possible, by putting in place plans to increase the retirement age for both men and women to 70, within the next decade. Although the upshot of Lord Turner's pensions report was that the state pension will eventually be awarded only above the age of 68, these reforms are due to come in completely only within four decades. Barrell's proposal is to bring in the increase far faster.

"Working longer makes a lot of sense and will cut the deficit," he says. " Society has to decide we will all work longer. Then we will have the tax revenue to help pay off the debt. It's not a quick solution. It raises revenue only slowly and cuts pensions costs only slowly but will ultimately bring the books back into balance."

It also has the advantage of not imposing a potentially economically damaging tax rise as the UK emerges from recession. However, the likelihood of either political party supporting such a proposal is highly doubtful.

No comments:

Post a Comment